Runaway Mitochondria Cause Telomere Damage in Cells

Using a technology developed by Carnegie Mellon University's Marcel Bruchez, researchers at UPMC Hillman Cancer Center have provided the first concrete evidence for the long-held belief that sick mitochondria pollute the cells they're supposed to be supplying with power.

The paper, published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, involves a causal experiment to kick off a mitochondrial chain reaction that wreaks havoc on the cell, all the way down to the genetic level.

"I like to call it 'the Chernobyl effect' -- you've turned the reactor on and now you can't turn it off," said senior author Bennett Van Houten, professor of pharmacology and chemical biology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and UPMC Hillman Cancer Center. "You have this clean-burning machine that's now polluting like mad, and that pollution feeds back and hurts electron transport function. It's a vicious cycle."

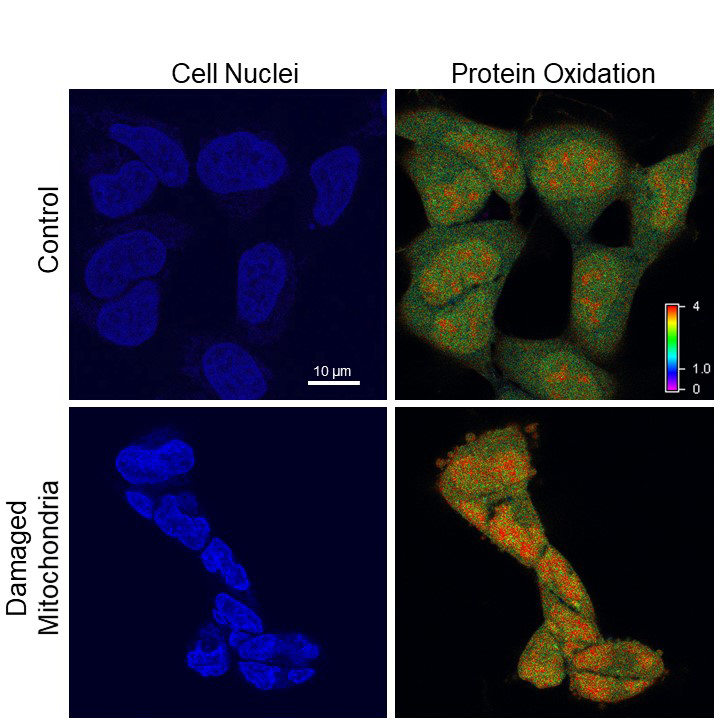

Van Houten's team used a new technology invented by Bruchez, professor of biological sciences and chemistry and director of the Molecular Biosensor and Imaging Center at Carnegie Mellon University, that produces damaging reactive oxygen species -- in this case, singlet oxygen -- inside the mitochondria when exposed to light.

"That's the Chernobyl incident," Van Houten said. "Once you turn the light off, there's no more singlet oxygen anymore, but you've disrupted the electron transport chain, so after 48 hours, the mitochondria are still leaking out reactive oxygen -- but the cells aren't dying, they're just sitting there erupting."

At this point, the nucleus of the cell is being pummeled by free radicals. It shrinks and contorts. The cell stops dividing. Yet, the DNA seems oddly intact.

That is, until the researchers start looking specifically at the telomeres -- the protective caps on the end of each chromosome that allow them to continue replicating and replenishing. Telomeres are extremely small, so DNA damage restricted to telomeres alone may not show up in a whole-genome test, like the one the researchers had been using up to this point.

"If you imagine the chromosome as a car, the telomere would be the width of its license plate," said study coauthor Patricia Opresko, professor of environmental and occupational health at the Pitt Graduate School of Public Health and UPMC Hillman.

So, to see the genetic effects of the mitochondrial meltdown, the researchers had to light up those tiny endcaps with fluorescent tags, and lo and behold, they found clear signs of telomeres' fragility and breakage.

Then, in a critical step, the researchers repeated the whole experiment on cells with inactivated mitochondria. Without the mitochondria to perpetuate the reaction, there was no buildup of free radicals inside the cell and no telomere damage.

"Basically, we shut the machine off before it had a chance to do any damage," Van Houten said.

These findings could be used for improving photodynamic cancer therapy, which involves bombarding solid tumors with reactive oxygen species using light delivered with fiber optic cables, Van Houten suggested.

One thing his team discovered in the course of these experiments is that inhibiting ATM -- a protein that signals DNA damage -- magnified the damaging effects of the reactive oxygen species spewed out by the mitochondria. The cells not only shriveled, but also died.

By combining photodynamic therapy with ATM inhibition, it may be possible to design a system that effectively kills cancer cells with light, Van Houten said.

Other authors on the study include Wei Qian, Namrata Kumar, Vera Roginskaya, Elise Fouquerel, and Shruti Shiva of Pitt; and Dmytro Kolodieznyi and Bruchez of Carnegie Mellon University.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R33ES025606 and R01GM017268), National Cancer Institute (P30CA047904) and the UPMC Aging Institute.